| |

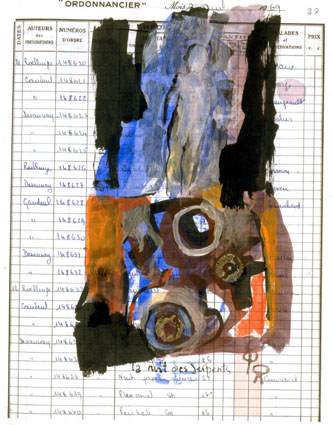

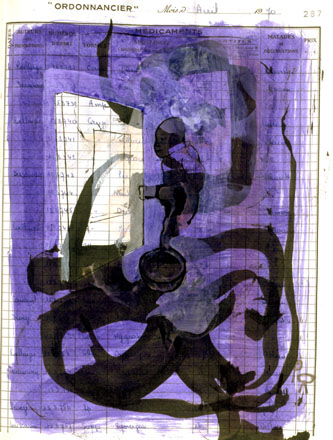

Round and round, the room turned his steps

ever towards its centre, as if he shuffled in an enormous bowl. |

| words |

john ricciardi art | patrick rocard music

| David Murphy |

|  |

| The

stairs loomed steep and ominous. Their wooden risers had been forbidden him after

a daughter had fallen and broken her hip. The floors above no longer were within

his day and night. | | |

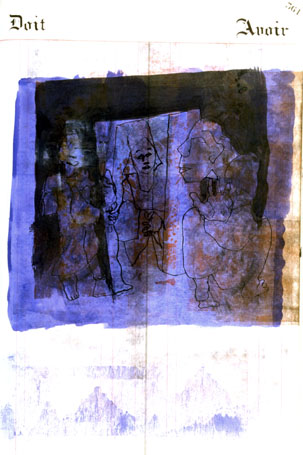

| "Papa

come out," his daughters called him. They had been alive more than seventy years,

he hardly less than a century. The two years since his wife's death had gobbled

up everything prior, crushed all other memories to non-existence with the pounding

of her absence like a jack-hammer on a steel plate, day after day: time beaten

flat. He aimed for the rear doorway, passed through into the yard, and squinted

at cold sunlight. Brisk autumn had hardened the grass, denuded the trees, and

strewn the lawn with leaves. He could walk easily; his legs were spry; but a few

paces on he stopped and began to waver. | |  |

| The

dead foliage, russet, sorrel, and maize, snagged in his vision, tipped brittle

into a flashing field of shifty, dry crabs with razor edges, or, where they tossed

together, floated turgid and sleek like the skin of a swamp. | |

| | In

and out, the wind picked through the weave of his trousers. His eyes were sharp

enough to allow him to shave; yet each morning he saw a proximate blear in his

mirror, spectral vapours for a head. He went back into the house as quickly as

he could. |

| | The

circuit from kitchen to salon to bedroom was too soon done. Even to his musician's

ears, melodies belied the promise of their initial summons to listen. All broadcasts

had become garbled, indistinct droning. Tobacco smoke wreathed him, went in little

clouds to nuzzle corners by the windows. |

| | "Stop

smoking Papa; it's time to eat." |

| God

had constructed him for duration. He had his teeth; yet the porcelain nibs were

keys to an ever-narrowing slot. He was caged in his thin bones, tethered in isolation's

cell. Taste had died; cooked meals long ago had become mere preludes to masticated

paste. Only the table wine, with its heavy sediment in the lees of the glass,

made sustenance palatable. | |  |

| "Wait

Papa." They spread newspaper sheets on the floor before the toilet. His daughters,

absolute rulers now, had less indulgence for their patriarch than would have rabble

for a monarch dethroned. The old man, in his own house, wasn't permitted a dog's

snap at dignity, not so much as a resentful snarl and an occasional, futile, mock

bite back. His hands shook; the newsprint smudged under a few stray drops. | |

| He

yet could read, but subject matter only gaped round the widening spiral where

his wife's soul had comforted his. | |

| | The

stories of the day wandered by him with no more import than the blue-grey smoke

staining his fingernails brownish ivory. Years before, when he still walked in

the street, a band of juvenescent toughs had roughed him up, taken his watch,

his wallet, and a silver pen, yet had missed his gold ring when he had turned

its shiny boss around his finger to face his palm. They terrified him with a coarse

brutality he never had seen in the young, returned a few small coins when he complained

that he no longer had any money with which to catch the bus home, and left in

his belly a burn of fearful anger when they had gone. |

| | On

and on within the measured confines of a beating heart, he circled and smoked,

circled and smoked, save for the few hours a night he lay in his bed. There the

ceiling dropped to within a touch of his forehead; the bedclothes billowed huge

and pale as a sea of sand. He shrank away then, lost his way, and floated as if

on a shingle in a fog. His daughters ... he called his daughters for the thousandth

time to fish him out, to carry him into morning. He was lost like that now, although

a clicking roar like gravel rolling in a river, stones spilling on the shore,

drowned his resolve to shout. The slough spun him giddy, then sliced fast and

hard towards a breakwater. Here was a clean fissure across the filmy murk, through

the opaque phlegm pulling apart. His daughter came into the room, listened to

the death-rattle, and once it had ended, shut her father's upturned eyes.

|

| | | |

|

| |

| | | |

| | | © Copyright 2001 Longtales Ltd All

Rights Reserved |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |